January 2024 | Volume 5, Issue 1

By Kathleen Harris

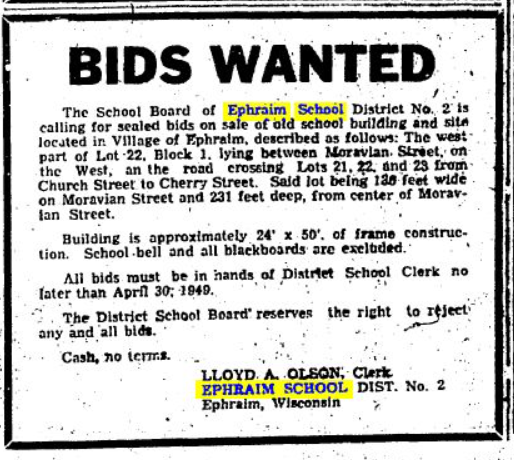

In the spring of 1949, Helen Hoeppner Sohns could not have imagined the consequences of her phone call to Warren Davis. Sohns was a long-time teacher at Ephraim School. Davis was a friend and summer resident who had become part of the fabric of Ephraim over many decades. With a note of urgency in her voice, Sohns told Davis that the village board had voted to scrap the one-room schoolhouse. The board’s call for bids, advertised repeatedly in the Door County Advocate since January 1948, had yielded nothing. No one, it seemed, wanted the 24 x 50 foot frame building that had stood on Moravia Street since 1880.

On the other hand, there was great enthusiasm for the new school, built up the road on Church Street (Hwy Q) at the corner of Norway. The site was level, unlike the old school that was tucked along a hillside making for “a very poor and dangerous playground for the children.” Each new class room measured 24 x 40 feet, nearly as big as the entire old schoolhouse. There was a drinking fountain, too, and room for a library. Nifty “florescent bulbs for dreary days” added a contemporary touch, having been sold commercially for just a decade (1938, The History of Florescent Lights). It seemed a great improvement compared to “the old school and its cross lighting.”

Parents, in turn, were happy about the new oil furnace with steam heat that guaranteed an even temperature throughout the building, though truth be told a few young rascals would miss dropping crayons through the old school’s iron floor grate, onto the furnace below.

Speaking of flooring, how about the new building’s modern, easy-care asphalt tiles instead of old-fashioned hardwood planks milled from local trees. Asphalt tiles, invented around 1920 as a by-product of asbestos mining, seemed just the ticket for easy care. They were in fashion nationwide and would remained so until non-asbestos vinyl tiles became standard in the 1980s, with help from the EPA.

Teacher Helen Sohns surely appreciated the conveniences of the new building and recognized the changing needs of classrooms and students. And yet, it didn’t feel right to dismantle a place that had created generations of memories. Was she remembering the many children who had walked up the path from Moravia Street and stepped through the schoolhouse door?

All of them had taken turns tugging on the faithful bell, and heard its clang of welcome. All had practiced sums on the chalkboard and, at day’s end, gone outside to clap dusty erasers. The schoolhouse was where Ephraim’s children first learned how to compromise with neighbors, practice kindness, and learn that success and taking accountability can feel good, in different ways. The one-room schoolhouse represented what Ephraim strived to be: a community that was welcoming, hard-working, honest, and resourceful. And fun! Goodness, who could forget the budding thespian talent on display at countless schoolhouse pageants and plays.

The old school was more than a building. Embracing progress didn’t mean you simply chucked the past. Did it?

The building Sohns wanted to save wasn’t Ephraim’s first school. In 1857, Rev. Andrew Iverson, the Norwegian minister who established Ephraim as a Moravian community a few years before, was elected Town Superintendent of Public Schools. It was a good fit given his Moravian belief in creating an engaged citizenry through education.

capacity from sixty to eighty children. Nellie Noble is identified as the teacher.

At the time the Township of Gibraltar included Ephraim, Fish Creek, Egg Harbor, and Baileys Harbor. Each town had its own school. Ephraim (District #4) representatives quickly met and voted to levy a tax for $120 to build a log building on land Iverson donated.

Larsen appointed first teacher. She was the daughter of Ole Larsen, who met Iverson in Buffalo, New York when the Moravians were journeying to Wisconsin. Pauline was a married teacher, uncommon at the time. She had 35 pupils her first year and earned $4 a week. Ephraim’s first school still stands on Willow Street and is privately owned.

As the village grew, so did the number of students. Twenty years later, a larger school was constructed for $658. This was the building that Helen Sohns was determined to save, the one that was in such a precarious predicament and in danger of being dismantled. When she phoned Warren Davis in the spring of 1949, she had just one question. Would he help her save the schoolhouse?

Find out in the next installment of 75th Anniversary Stories.

ALL CONTENT © 2024 BY DOOR GUIDE PUBLISHING

ALL CONTENT © 2024 BY DOOR GUIDE PUBLISHING