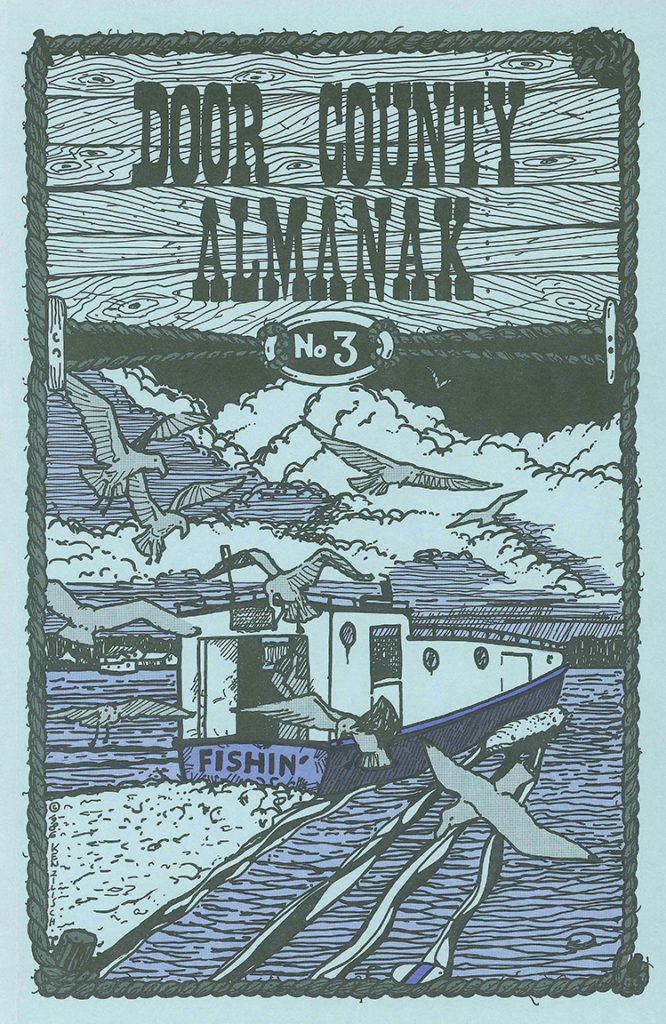

(Originally published in Door County Almanak No. 3, by Dragonsbreath Press)

By James B. Hale

Anyone who has lived in a small town and is old enough to remember times before radio and television became a way of life knows the joys the local post office could bring. It was the nerve center of the whole community. The distribution of the daily mail was the time for a gathering of all those who were curious about the delights and sorrows their lock-box might hold, or who wished to swap gossip with their neighbors.

This event is as true in Door County as elsewhere. Elsie Anclam, a daughter of a Baileys Harbor postmaster, wrote about how it was at the turn of the century:

In the autumn of 1892, my parents came to Baileys Harbor where they purchased the store of Augusta Wohltman. The following spring, they moved into the large white building to operate the general store and post office until 1914. The mail, in those days, was carried by a wagon in summer; it was known as “the stage.” In winter, a sleigh was used with a coal stove supplying the heat. The post office cabinet occupied a corner of the store and when the mail arrived, late in winter due to snowbound roads, the crowd gathered around, making considerable noise, sometimes unnerving the postmaster trying desperately to sort the mail.

Similar scenes, varying in detail but not in plot, had been going on in Door County for nearly 50 years.

The United States Post Office Department did not officially come to Door County until June 22, 1854, when the first regular office opened at Washington Harbor on the north end of Washington Island. Before that date, the mails were irregular and undependable. Settlements were few and were confined to the shores of Lake Michigan and Green Bay.

The county itself was only three years old, having been organized by the Wisconsin legislature in 1951. There were no roads inland. The nearest post office was at Green Bay, where the first post office in what is now Wisconsin had been established in 1821. However, a trip to Green Bay was not easy since it involved a 100-mile journey by boat in the summer or on foot over the ice in winter.

H. R. Holand wrote of the people on Rock Island in the early 1840s:

Their chief handicap was their distance from any post office through which to learn the news of the outside world. The most accessible one (and the one with better connections to the east than Green Bay) was at Chicago, 300 miles away. Mail intended for the settlement was usually directed as follows: “H. D. Miner, Rock Island, care of Williams, Chicago, Illinois.” On his occasional visit to the metropolis, Job Luther would get the little bundle of Rock Island letters and newspapers, often many months old.

By the 1850s, the fishermen on Washington and Rock Islands were having mail brought to them from Green Bay in the summer months by the fish buyers who made weekly trips by boat. In the winter, however, the people who stayed on the islands were left to their own devices. They chose H. D. Miner, son of the first Protestant missionary among the Indians in Wisconsin, to make an occasional trip to Green Bay on the ice. He safely hauled his sled loaded with mail and supplies up and down the Bay for 13 years. When the ice was in good condition, he made the round trip to Green Bay twice a month.

Mr. Miner also carried mail from Washington Island 12 miles north to St. Martin’s Island in Michigan. He was hired to do this by the St. Martin’s residents for 25 cents per letter or paper.

Winter brought a variety of problems. One of the early postmasters recalled an incident when the Washington Islanders went seven weeks without mail due to stormy weather. Finally, a man was found to make the trip to Green Bay, not only because of the mail but because the whole island had run out of chewing tobacco.

In the fall of 1856, the first road was cut through the woods from Sturgeon Bay north 15 miles to Egg Harbor, and in the following winter, another road was opened up from Sturgeon Bay south to Green Bay. This made more frequent communications possible between the county and the rest of the state, and a demand for postal service was soon followed by the establishment of more post offices. Sturgeon Bay in 1855 and Fish Creek in 1858 were the county’s second and third offices. By the end of 1862, the county had 12 post offices.

The early post offices were usually housed in the postmaster’s home. Holand offered this description of the first post office in Ephraim during the 1860s:

There was nothing impressive about this post office. It was confined to a small shelf in a corner of Hans Jacobs’ one-room cabin. On this shelf stood a tin box about a foot square and six inches deep. This was the office itself and was treated with profound respect by all as being dedicated to the service of the U.S. Government. It was always kept carefully locked, and Mr. Jacobs would never permit anyone but himself to touch the sacred treasure chest. The contents of this box were rather disappointing. It had two compartments, in the smaller of which was about a dollar’s worth of stamps and a pamphlet of post office regulations. The large compartment was intended for outgoing and incoming mail but was usually empty, for the pioneers of Ephraim very seldom wrote or received letters.

By 1880, postal services had expanded greatly. There were 24 offices in the county that year. Charles Martin, writing in 1881, reported:

From Sturgeon Bay, the county seat, mails and express make daily connections with railroad routes at Green Bay. All over the county but a few miles apart, are established post offices, conveniently located for settlements and settlers. Mail matters are carried to the post offices by stage lines, and parties desiring to reach any part of the county can secure passage in the mail coaches at reasonably low prices.

As a matter of record, the “coaches” were more often than not a horse and wagon or buggy.

In the early years, it seemed to be a status symbol to obtain a post office for your community, become its postmaster, and have it named after yourself. At least eight of the county’s offices bore the names of the first postmaster. For example, Marcus McCormick was the first postmaster at Marcus, the village that later became Forestville.

Foscoro was another example. The name was coined from the names of the three men who founded the village—Foster, Coe, and Rowe—and one of them, George Rowe, was the first postmaster. Other offices named in this way included Duchateau, Stokes, Voseville, Horn’s Pier, Stevenson’s Pier, and Wililamsonville.

The postmasters’ reward almost certainly had to be status, since it was not money. AT Stokes, for example, the postmaster, Charles Stokes, had an annual salary which ranged from $15 to $53 during the first five years of his tenure.

At one time or another, there have been 48 named post offices in Door County. They were most numerous between 1880 and about 1900, the period of rapid rural settlement when it was Post Office Department policy to have offices located so that no one had to go more than just a few miles to get their mail. The peak year for numbers was 1902, when there were 36 post offices in operation at one time. Shortly thereafter, Rural Free Delivery was started from several of the larger villages, and the small country offices were closed.

By 1910, only 13 offices remained. Since then, Maplewood was re-established in 1914 (after closing in 1904), Washington Harbor closed in 1916, Sawyer closed in 1938 to become a branch office of Sturgeon Bay, Jacksonport closed in 1970, and the remaining 11 are still handling all the county’s mail: Baileys Harbor, Brussels, Egg Harbor, Ellison Bay, Ephraim, Fish Creek, Forestville, Maplewood, Sister Bay, Sturgeon Bay, and Washington Island.

As the county was settled in the last half of the 19thcentury, post offices were closely involved with the county’s life. Sometimes a post office preceded a place rather than the usual other way around. Martin described an example:

In 1856, Mr. Nelson W. Fuller, and others, wanted a post office on the west side of Sturgeon Bay. As to a name for the P.O. to be established, the Post Office Department at Washington did not agree with Mr. Fuller and other parties here, so the whole matter concerning the name was left with the postmaster at Green Bay, who thought that “Nasewaupee,” the name of a Menominee Indian chief that once located thereabouts, was appropriate.

Nasewaupee post office flourished under Mr. Fuller’s administration as postmaster. At least we presume it flourished, for his net earnings the first three months were 37 cents. He finally resigned the position of postmaster in favor of his brother. Mr. E. S. Fuller, who kept up the office for a time, when the post office came to the same end as did Chief Nasewaupee—passed from existence.

When Nasewaupee township was formed by the Door County Board in 1859, it was named after the post office, and now the name “Nasewaupee” lives on, and only time will tell how far up the ladder of fame it will climb.

It is not certain yet how far Nasewaupee has climbed; at least it has not fallen off, since the township is still flourishing.

The community of Belgian settlers in the southern part of the county has a volatile one. From 1870 to 1890, there was a period of religious unrest among the Belgians that involved at least three post offices, Leccia, Minor, and Namur.

In these years, religious feeling was intense. There was a Spiritualist and an Old Catholic movement. Opposition factions resorted to violence on occasion; there are stories of fistfights in churches during Mass and of priests being chased down the road by their detractors.

The Leccia post office was established for and named in honor of Father Erasmus Leccia, who started an Independent Catholic Society based on the rejection of Papal authority, and who built St. Michael’s Church south of Brussels. The office, which was located next to the church, operated from 1880 through 1885.

In 1882, when Father Leccia became reconciled with the Roman church, some of his indignant parishioners refused to give him the opportunity to see their mail, so they secured the Minor post office located about a half a mile east of Leccia. They named it for E. S. Minor, a distinguished Sturgeon Bay businessman and Democrat politician who helped secure the office. It was in existence for slightly more than two months, the shortest life of any Door County post office.

There were religious problems at Namur, too. The Door County Advocatefor February 18, 1879, reported that “the Namur post office has been discontinued by the post office department because of improper handling of the mails—they weren’t as ‘contraband’ as they should have been.” The office allegedly was closed because of censorship exercised by the local Catholic priest over the mail. However, the Namur office re-opened in March 1879, presumably under new management. It finally closed in 19045 with the advent of Rural Free Delivery from Brussels.

Deep tragedy was also recorded with the post offices. The settlement of Williamsonville was established by and named for the first postmaster, John Williamson, in January 1871. The following October, this community was a victim of the catastrophic firestorms that swept much of southern Door County as well as much of northeastern Wisconsin, including the famous Peshtigo fire that killed 1,500 people. At Williamsonville, 61 of 78 residents, including the postmaster, lost their lives. In January 1872, the name of the post office was changed to Tornado to commemorate the great fire. The office was discontinued in 1907, but the site of these events remains as Tornado County Park on Highway 57 south of Sturgeon Bay.

It has been said that Door County had an uncommonly high proportion of colorful characters in its early history. This was partially attributable to the fact that most of the settlers were fishermen and lumberjacks, who were unpredictable folks at best. At any rate, this tendency was reflected in some of the post office names. The present village of Gills Rock at the north end of the Door Peninsula is a good example. It was originally known as Hedge Hog; this was the name of this post office when it was established in 1883. Gills Rock did not come into official use until 1902.

Martin described the origin of Hedge Hog:

A comical genius by the name of Lovejoy was an old bachelor that lived in the county for some time. He had been away from the society of women so long that the sight of one would make him jump as if struck by electricity, and he would run off into the woods. However, sometime afterward, he became more reconciled, and finally got so close to a woman as to marry her.

He was the first shipbuilder in these parts. He built a small vessel at Big Sturgeon—scoop-rig, good model, and fine sailer. The craft was used for fishing and freighting about the islands. The first winter after she was launched, he laid her up in a little inlet about a mile or so from the Door bluffs. The water fell so much that winter that he could not get the boat afloat the next spring. During the summer, the porcupines gnawed several holes in her, which gave rise to the place being called Hedgehog Harbor.

And so it remained.

Another pioneer personality was William H. Horn. He was engaged in a variety of businesses along the Lake Michigan shore from Chicago to Baileys Harbor in the 1870s and ’80s. He built his own private telegraph line from Algoma to Baileys Harbor in the ’70s. He built a pier on the lakeshore north of Sturgeon Bay and named the settlement around it St. Joseph in honor of his business partner. However, when the partnership dissolved, Mr. Horn changed the name to Lily Bay after his daughter, Lily. He was responsible for the establishment of the post office at Horn’s Pier, one of his business ventures in the Town of Clay Banks, and became its first postmaster. When the pier failed, Mr. Horn left Door County for the west and did not return.

The history of the U.S. Mail in Door County never can be written completely. Source materials are scattered, sketchy, and inconsistent in details. But this is what makes the search interesting. The unknowns become a challenge.

Why was Malakoff chosen as a post office name when there were apparently no Russian settlers or other Russian influences in the county at the time? Who or what was the Hastings for which the Hastings post office was named? Why was the Institute post office moved from the St. Alysius Orphanage to Wester’s Saloon? What is the story of Benjamin Minsker, who held four different postmaster appointments in two different villages?

Little by little, pieces fall into place as some unexpected lead to an historical fact comes to light. This just enough to keep the amateur historian going. It’s a long but fascinating road ahead.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

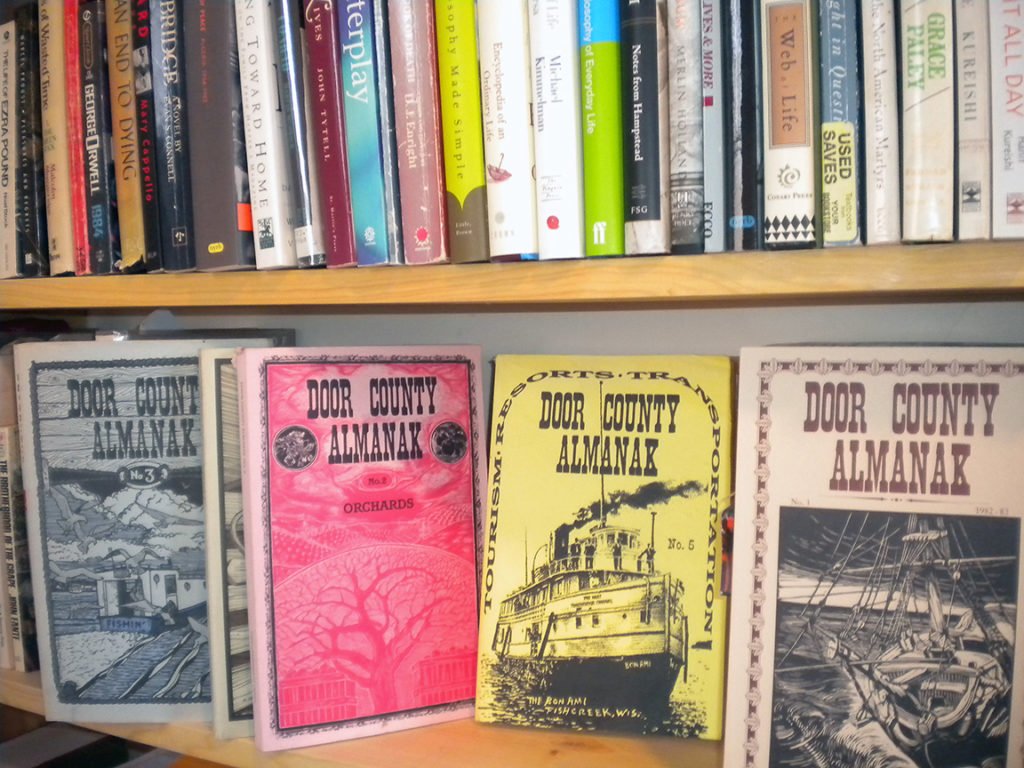

In the early 1980s, Kevin Wade Combes and Fred Johnson conceived the idea for a “new journal for published authors/poets, as well as yet-to-be-discovered talents.” The result was the Door County Almanak series, published by The Dragonsbreath Press, which was ultimately issued in five editions over the next ten years. With the exception of No. 1, each Almanak had an overall theme, which they each cover “in considerable detail and from many different angles,” as noted by Wisconsin rare book dealer Charlie Calkins. The edition themes are — No. 1: general Door County topics; No. 2: Orchards; No. 3: Commercial Fishing; No. 4: Farms; No. 5: Tourism/Resorts/Transportation. The Almanak series has been out-of-print for almost 20 years, but is still available in limited quantities from Charlie Calkins, The Badger Bibliophile, Olde Orchard Antique Mall, Egg Harbor, 262.547.6572, wibooks@yahoo.com.

ALL CONTENT © 2024 BY DOOR GUIDE PUBLISHING

ALL CONTENT © 2024 BY DOOR GUIDE PUBLISHING