(Originally published in Door County Almanak No. 3, by Dragonsbreath Press)

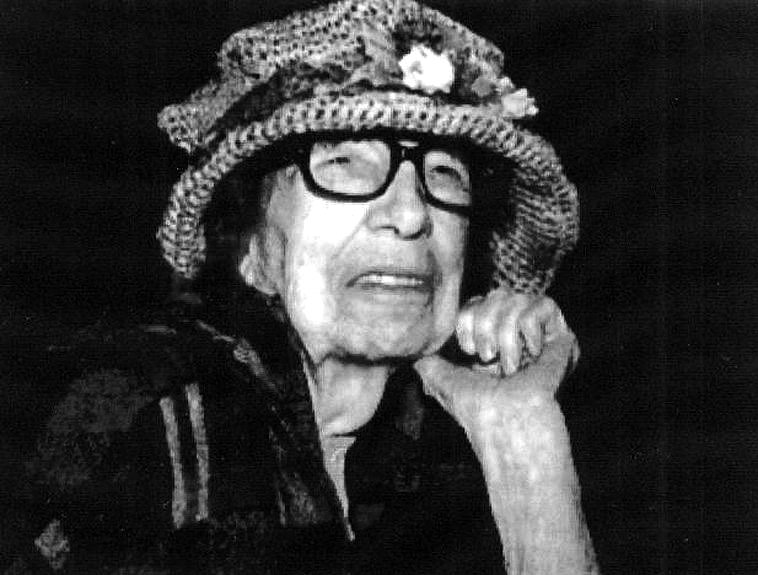

By Frances May

Fifty years ago, I learned what it was like to live in the teeming household of a fishing family. The Joe Mays supplemented their farm income with winter carp fishing in the bays, bordering on Nasewaupee township.

There were nine people eating and sleeping in the farmhouse the winter of 1934 and 1935. There were two young married couples, Joe, Jr. (“Joey”) and I, his sister Joyce and her husband, Ben Denil. Lloyd, Joe’s 18-year-old brother, slept on a single bed in the smallest bedroom, which was the storeroom in less populous times. The fourth upstairs bedroom was shared by the game warden and the fish buyer’s agent. The only bedroom downstairs belong to Pa and Ma May: Joe, Sr. And Amelia Gustafson May.

Amelia was the soul and the inspiration that launched the fishing venture. She came from an ancestry of fishing people. Carl (Charlie) Gustafson, was born in Sweden. He and his son, Clarence, had a boat and fished the bays for whitefish and trout.

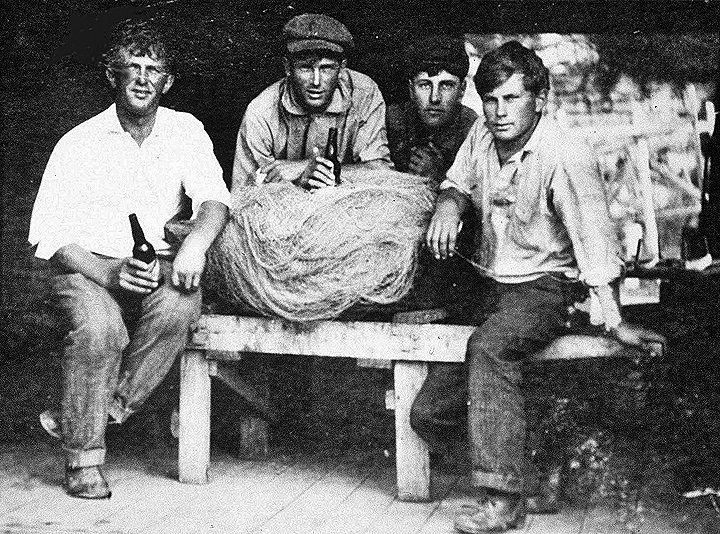

It was the time of what was later called The Great Depression. Traditionally, the Mays were farmers, as the Gustafsons were fishermen. Amelia talked Joe into the initial venture. They bought twine and corks and made lead weights for carp nets. Amelia taught Joe how to string the nets. Her brother, Clarence, joined them in a partnership that lasted a few years until Clarence bought his own nets. By that time, young Joey had learned the crafts and skills and was able to really help his parents. It was hard work in the coldest weather but it brought money into the house.

My first winter in the May household in ’34 to ’35 was an eye-opener. I was brought up on a farm in Michigan and knew nothing about fishing. Besides that, my mother was an avid reader, an embroiderer, and a flower garden enthusiast. No woman in our neighborhood did any farm chores or outside work. She was horrified when I wrote her the proud news that in these busy times, I was helping out with the milking. The Mays took it for granted.

Joe’s parents leaped out of bed when the alarm clock announced 5 o’clock. Pa made fires in the living room heater and the cook stove. (In the coldest weather, a chunk of the hoarded coal would keep a bank of glowing coals alive overnight.) Ma would be scurrying between the pantry and the stove, setting up oatmeal and pork sausage.

If Pa didn’t hear footsteps overhead from the rooms occupied by the younger marrieds, he would rap on the ceiling with the broom handle.

At the breakfast table, he might inspire blushes when he fixed me with an eagle’s eye, saying, “No lollygagging around here in the morning.”

That winter, Amelia did not go out on the ice every day with the men Joyce was expecting her first child in January. The family agreed that Ma should stay home unless there was an emergency. By emergency, Pa meant a big run of carp.

When there was a big school of carp in Sand Bay or Little Sturgeon Bay, they went out on the ice in two crews. Ben Denil worked with Pa. Ma and Joey were the other partnership. Lloyd took care of the barn chores.

I asked my father-in-law why Ma always went along with Joey. It seemed to be taken for granted that they should work together.

Pa’s dark eyes twinkled. He had a wry sense of humor and often made light but perceptive comments to my frequent questions about the fishing operation.

“Joey don’t get along too well with the hired men.”

“Why not?”

Pa explained, “He expects the hired man to run from one hole to the next. Joey says that he can’t work with a man that don’t run.

I was horrified. “You mean he expects his mother to run all day long on the ice?”

Pa laughed. “She can out-run Joey. She can out-run me. Ma’s a born fisherman.”

Amelia didn’t run in the house, but she got around in a hurry. Twice a week, she baked nine huge, brown crusted loaves of bread, mounds of oatmeal or molasses cookies. A basket of food was packed daily for noon lunch on the ice. The two quart syrup pail of coffee would be heated again on the stove I the fishing shanty.

A length of clothesline rope was strung across a corner nearest the kitchen stove. Mittens and socks were hung there to dry. There was a similar line behind the living room heater. Tire trouble on one of the two trucks meant that Lloyd would set up indoors to change or patch the inner tube on the linoleum floor in front of the heater. I mopped sitting room and kitchen linoleums every day with hot water from the kitchen range reservoir, using plenty of Ma’s homemade yellow lye soap. The fishermen wore knee high rubber boots from five in the morning ’til bedtime. Ma wore boots most of the time, too. She helped Lloyd milk the cows. She tended the chickens. When I carried water from the pump house or hauled wood from the shed, I wore galoshes over my oxfords. The snow was well trampled in the May yard with boots, trucks, Joey’s homemade snowmobile, three dogs and uncountable barnyard cats. Amelia’s pet sheep, Nanny, stayed in the barn all winter. When Ma sat down in the evening, she darned socks and mittens with yarn spun from Nanny’s wool fleece.

On the 14thof January, 1935, Door County was in the throes of an old-fashioned blizzard. The men had a late start because Lloyd, driving too close to the gas pump, knocked a runner off the model A Ford Joey had converted to a snowmobile. While Joey and Ben made the necessary repairs to the machine, Lloyd disappeared into the safe haven of the barn. Pa stomped in and out of the house, the blizzard blowing past red mackinawed shoulders. Joyce swept up the clots of snow from his boots. Ma handed Pa the basket of lunch and a shoebox filled with dry mittens and gloves. They left after 10o’clock, Pa advising us not to expect them back too early.

Neither Ma nor Joyce felt well that day. Ma was suffering from a too frequent toothache. She yielded to daughter and daughter-in-law, swallowed a couple of aspirins and laid on the couch with her cheek on a hot water bottle and a wooly afghan tucked around her ample body. No one knew the pain was caused by a “strep” infection that would lodge in her heart valves. It was Amelia G. May’s last winter.

Joyce was uncomfortable and restless all day. She baked Ben’s favorite cookies and hemmed flannel squares foe diapers, frequently glancing out one window or another into the swirling snowstorm. She wished the men would come home. It was always worse on the ice. What if they were stranded? What if the damaged snowmobile broke down? The men came home around six o’clock, the snowmobile chugging and clanking. They were snowy, red faced, and loudly exhilarated. Their supper was waiting. At the table, Pa and Joey told Ma in detail about the mishaps and the triumphs of the day. May had been half asleep all day from boredom and pain killer. Now she was wide awake. I could see where her heart lay. As Pa expressed it, she was the real fisherman of the family.

Joyce washed the supper dishes, I dried them. She was pale, quiet, and seemed preoccupied. Afterward, we both went into the sitting room where the fishermen were reading newspapers, listening to the radio, or gazing out the windows into the snowy blizzard. It had not abated.

Joyce whispered to Ma who sat in a rocking chair darning socks. Ma leaned forward and whispered to Pa who was reading the daily newspaper. Joyce whispered to Ben who stood at the window. Ma’s marquisette panel clutched back from the pane. The curtain fell out of his red first. Is mouth looked like a soundless whistle.

Pa said, “Well have to call the doctor.”

Joyce said, one hand guardedly against her side, “What doctor?”

“Konop, of course,” Pa said, folding the paper as he stood up. “Who else is there?”

Fortunately, the storm had not damaged our telephone lines into town, but Dr. Konop was not available. He was out on another call. Mrs. Konop advised Pa to call the new young doctor. She gave Pa his telephone number which was not yet in the book.

The county snowplow preceded Dr. Muehlhauser to the May schoolhouse, where Joey met him with his snowmobile. Joey towed the doctor’s Buick a mile and a half through snow banks and swirling snowflakes. The bitter northern wind whipped his face when he had to put his head out of the window to see the road ahead.

By the time they arrived, Joey carrying the doctor’s official black bag, Ma and I had changed the bedding in the first floor bedroom and tucked Joyce into Ma’s bed. Pa and Lloyd were listening to the radio and reading the paper like nothing unusual was happening. Ben, the prospective father, was walking the floor, looking out the window, and trying to keep out of our paths. The copper boiler steamed around the edges of its lid. The kitchen stove crackled and hissed. Ma had said the copper boiler might have a small leak.

Merlyn Denil was born about 5 o’clock in the morning on January 15, 1935, seven pounds five ounces with lots of black hair. Before Ben had the opportunity to hold his baby, the new grandmother passed the flannel wrapped newcomer over to his grandfather as if for inspection.

Pa nodded approval and handed the baby to Ben. Pa touched the damp black curls. “He looks like all the May babies,” he said, reaching for his boots. He smiled slyly at his elder son. “Excepting you, Joey. You’re a Gustafson with your blue eyes and white hair.”

In the sitting room, May and I had opened the big table with three inset leaves. Her bleached flour-sacking tablecloth had been spread over the everyday oilcloth in honor of the doctor’s presence, but the repast was the usual hearty meal.

Doctor Muehlhauser stood in the doorway between the kitchen and sitting room. There was beef steak and gravy, butter fried potatoes, applesauce, apple pie, doughnuts. There was a long platter of crusty velvety white bread and lemon yellow home-churned butter, two kinds of jelly, wild grape and loganberry.

The doctor said, “It this festlich bewirten in celebration of your first grandchild?”

“Oh, no.” Amelia had a warm chuckle. “This is usual. Our men need a good start for a long day on the ice. At noon they have a cold lunch. Supper is a long way off.”

Two days later, Joey’s mother and I baked all day and did a big washing. Amelia planned to go out on the ice the following day. The men had set more nets. The storm, as usual, had stirred the fish to action, and there was a school of carp moving in Riley’s Bay. Joey needed his partner on the second crew on the ice.

When I pinned the new diapers to the clothesline, they froze in my finger sand flapped in the wind like sheets of paper.

Indoors again, I toasted my hands near the heater. The telephone rang and I had some advice from a neighbor to the north who could overlook our back yard.

“Are you crazy over there? It’s 26 below zero. Do as I do. Hang those didies in the attic.”

Joey’s mother was scornful. “It’s the easy way. In a fishing business, you learn early there’s two ways to do a thing, the easy way and the right way. You find that out when somebody ties the anchor lines quick and easy. By the next morning, your nets might be hooked up on a reef or God knows where.”

I picket up the laundry basket to carry the wet things to the lines. She had folded them and laid warmed clothespins in the corners to make my job easier.

“Diapers freeze white as new snowfall,” she said.

Amelia Gustafson May died in October of that year. It was her last year as the heart and soul of the May fishing family. We often speak of her. She is not forgotten.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

For many years, Sturgeon Bay resident Frances May was “Door County’s ‘Unofficial’ Poet Laureate” and was published in Norbert Blei’s Cross+Roads Press (e.g. The Rain Barrel, ©2005) among other venues. The above story was first published in Door County Almanak No. 3, by The Dragonsbreath Press. In the early 1980s, Kevin Wade Combes and Fred Johnson had conceived the idea for a “…new journal for published authors/poets, as well as yet-to-be-discovered talents.” The result was the Door County Almanak series, published by The Dragonsbreath Press, which was ultimately issued in five editions over the next ten years. With the exception of No. 1, each Almanak had an overall theme, which they each cover “in considerable detail and from many different angles,” as noted by Wisconsin rare book dealer Charlie Calkins. The edition themes are — No. 1: general Door County topics; No. 2: Orchards; No. 3: Commercial Fishing; No. 4: Farms; No. 5: Tourism/Resorts/Transportation. The Almanak series has been out-of-print for almost 20 years, but is still available in limited quantities both from Charlie Calkins, The Badger Bibliophile, Olde Orchard Antique Mall, Egg Harbor, 262.547.6572, wibooks@yahoo.com, and online at the Sister Bay Historical Society website: www.sisterbayhistory.org.

ALL CONTENT © 2024 BY DOOR GUIDE PUBLISHING

ALL CONTENT © 2024 BY DOOR GUIDE PUBLISHING